I’ve been afraid to say this for a while because of how it will be perceived, but my favourite book of all time is actually a textbook. So before you think that makes me someone you would never want to speak to, I’ll ask if you have ever read anything by Irvin Yalom, American Psychiatrist and Author?

His book ‘Existential Psychotherapy’ is a true masterpiece he worked on for 10 years and is written as eloquently as any of his other titles, including ‘When Nietzsche Wept’, the best fiction novel award winner in 1992.

What is Existential Psychotherapy?

Existentialism is the philosophical exploration of existential issues or questions about our existence that we don’t have an easy answer for. We all suffer from anxiety, despair, grief and loneliness at times in our lives. Existential Psychotherapy tries to understand what life and humanity are about.

In the book, Yalom explores what he considers to be our four most significant existential issues in life:

- Death

- Freedom

- Isolation

- Meaninglessness

These existential issues or ultimate concerns are “givens of existence” or “an inescapable part” of being an alive human in our world. He shows how these concerns develop over time, how we can run into problems with each of these issues, and what they might look like in patients coming to therapy. He also talks about how we can try to live with these concerns to negatively impact our lives less, even if we don’t have clear-cut solutions to them.

Let’s go through each of these ultimate concerns…

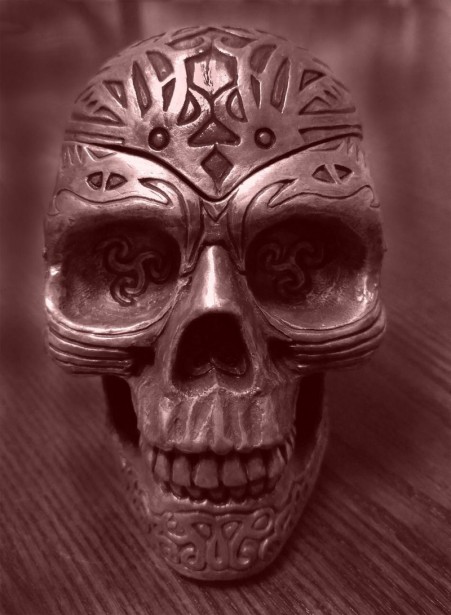

1. Death

Homo sapiens, or humans, as far as I know, are the only species in the animal kingdom that are aware that one day they are going to die.

The first time I heard this, it fascinated me and made me wonder if life would be more comfortable not being aware that one day we cease to exist.

Imagine it. Life is going well. Then suddenly, it is no more. No worry about what the future holds. We are born. We experience life. Then we are no longer there. No fear. Just nothingness.

Being aware that we will die shapes and influences our lives much more than we would like to admit. This is because so many of our anxieties and phobias at their core are fear of some loss or death.

Irvin Yalom says that while the actuality of death is the end of us, the idea of death can actually energise us.

If we don’t know when we will die, being in touch with the fact that one day everything will vanish is enough to overwhelm some people and make them panic.

For others, it is enough to make them follow the maxim of carpe diem and helps them to seize the day by appreciating everything they have so that they can make the most of the precious time they have left on this planet. Time is really just a bright spark of lightness between two identical and infinite periods of darkness — one before we are born and one after.

Death is the ultimate equaliser, for no matter how much we have achieved or done with our time on this planet, the truth is that we will all one day die.

It is also true that we will not know exactly when death will happen. It might be with a car accident tomorrow, from cancer in ten years, motor neurone disease in twenty years, a heart attack in thirty years, a stroke in forty years, or during our sleep in fifty years.

Because our knowledge of our inevitable death is so inescapable and hard to confront and deal with directly, we instead focus on smaller and more manageable worries or concerns in our lives that we can do something about if we want to. If we successfully address all these minor concerns, however, we then come in contact with our fear of death again, and the cycle repeats itself.

Most people tend to have one of two basic defence mechanisms against their fear of death:

A. They can think that they are “special” and that death will befall others but not them, and try to be an individual and experience anxiety about life.

Or

B. They can think they are an “ultimate rescuer” and try to fuse with others and experience anxiety about death (their own mortality and that of their loved ones).

A breakdown of either of these defences can give rise to psychological disorders:

- narcissism or schizoid characteristics for the “special” defence, and

- passive, dependent or masochistic characteristics for the “ultimate rescuer” defence.

In general, trying to be an individual is a more empowering and effective defence than fusing with others. Still, the breakdown of either can lead to pathological anxiety and/or depression.

The way to feel better about death anxiety is through an exercise called “disidentification”:

- To begin with, ask yourself the question “Who am I?” and write down every answer that you can think of.

- Then, take one answer at a time, and meditate on giving up this part of yourself, asking and reflecting on what it would be like to give up this part of yourself and your identity.

- Repeat this with all the other answers until you have gone through all of them.

- You have now disidentified yourself from all parts of your identity. See how you feel, and if there isn’t still a part of you, that feels separate from all the labels you give yourself. This provides comfort and reduces anxiety about death and life for a lot of people.

What I try to manage death anxiety is to only focus on whatever is most important to me that I can do something about in any given moment. I try to appreciate and be grateful for the time that I have had with each important person in my life. I try to be as fully present in the moment and with others as I can be. I try to use every moment and meeting as an opportunity to impact someone’s life positively. That way, I’ll hopefully not have too many regrets and be glad for the time I have had on this planet, no matter how long it ends up being.

2. Freedom

The second ultimate concern is about freedom, responsibility and will.

Every country in the world talks about fighting for the freedom of its citizens and about taking away some people’s freedom to ensure the safety and security of all. Therefore, the existential dilemma is how much freedom do we give up to others to feel safe and secure, or how much safety and security do we give up to feel genuinely free? Are these concepts in direct opposition, or is it sometimes possible to have enough of both?

Responsibility means taking full ownership of:

“one’s own self, destiny, life predicament, feelings, and if such be the case, one’s own suffering” — Irvin Yalom

In the past, one’s life was set out for them by their parents or society, and many people struggled to fight for the right to live an authentic and genuine life.

These days, most people struggle instead with the amount of choice that they have in their lives. They come to therapy because they don’t know what they want to do or how to choose, given all of the available options. They also know that if no one else is telling them what to do, it is ultimately their responsibility if things do not work out the way they want them to. People wish to choose for themselves but fear not having someone to blame when things don’t work out.

There are various defences that we engage in to avoid responsibility and shield ourselves from freedom, including:

- compulsivity

- displacement of responsibility to another

- denial of responsibility (“innocent victim” or “losing control”)

- avoidance of autonomous behaviour, and

- decisional pathology

We can do something over and over again to relieve anxiety or stop thinking about things. This can present as OCD, hoarding, or any addiction ranging from technology to drugs and alcohol and even dependency on others.

We can try to coerce others to make decisions for us or seek out and find controlling partners, bosses or friends. But, we can also play it safe and try to do what we think everyone else does; focus on keeping up with the Joneses, engaging in passive activities that don’t require much effort, and feeling stuck in an unfulfilling relationship or career.

The problem with giving up the responsibility for how our lives turn out is that it creates an external rather than an internal locus of control. Depression and other forms of psychological disorders are more highly correlated with an external locus of control. It can also lead to learned helplessness, where people no longer feel like they can do anything to change their life in a positive direction.

The way to manage the responsibility and freedom paradox is to develop an internal locus of control. This is generally more beneficial for most people’s well-being unless we blame ourselves or change things out of our control. This includes what has happened in the past, what other people do or say, and acts of nature.

The serenity prayer nicely spells out how we should approach responsibility:

“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.” — Reinhold Niebuhr

Paradoxical intention is a good antidote too. This means that we try to do the opposite of what we typically do for a period of time and keep an open mind and observe how things go. We can then see if the outcome is better than what we usually do or if it has taught us something about what will be best for us going forward.

Anything that creates a double bind is potentially helpful for encouraging people to take more responsibility in their lives. One way is to remind someone who struggles to make their own decisions that by not deciding, they are still making a choice not to choose. This means that no matter what they do, it is impossible not to make a decision that impacts the direction of their lives. Even if we choose to follow what someone else wants us to do, we still choose to do this. Therefore, why not take responsibility for our own lives and forge our own paths?

3. Isolation

There are three types of isolation:

“A. Interpersonal isolation: isolation from other individuals, experienced as loneliness

B. Intrapersonal isolation: parts of oneself are partitioned off from the self, and

C. Existential isolation: “an unbridgeable gap between oneself and any other being.”

A common way that people try to escape from existential isolation is to fuse with another fully. This is also a strategy for dealing with death anxiety, with people trying to be the “ultimate rescuer” of someone else. It can lead to an individual feeling temporarily less alone. Unfortunately, however, the less isolated we are from others, sometimes the more isolated we are from ourselves.

Other people try to overcompensate for their feelings of isolation by never relying on anyone and trying to be fully independent. Both extremes can have negative consequences.

The main thing we can do to manage our feelings of isolation is to realise and accept that we are social creatures and have always relied on others to survive. This drive creates a desire to feel closer to, more understood, and more connected to people than we can ever achieve and sustain.

Growing up, many people feel loved and comforted in an unbalanced relationship towards their needs being met over their parents. They then try to reenact this within their adult relationships and usually end up feeling resentful, angry and disappointed as a result.

Yalom believes that a good relationship involves “needs-free love”, which is about loving someone else for their sake. This is opposed to “deficiency love”, a selfish love where we only think about how useful the other person may be to us. Creating a relationship where you want the best for the other person is a healthier way to manage interpersonal isolation than demanding for them to meet every need for you.

Some of the best solutions to intrapersonal isolation are to have time to get to know ourselves through practices such as journaling, therapy and meditation. Introverts may need to have more of this time than extroverts, so it’s important to tune into how agitated or lonely you feel to know if you have found the right balance or not.

Unfortunately, existential isolation cannot be fully breached, and therefore needs to be accepted, as it is out of our control. To feel the pain that comes with this isolation and our desire not to have it is challenging, but it can help reduce the intensity of the feeling. Being grateful for the meaningful connections we have in our lives and trying to strengthen them without losing our sense of self is another way to lessen the intensity of the feeling.

4. Meaninglessness

According to Yalom and many non-religious philosophers, humans are meaning-seeking creatures in a world without a universal sense of meaning. As a result of this, most of the world turn to a religious or spiritual belief system of one type or another that clearly lays out the meaning of the world and our purpose in it. People who truly believe these systems often provide a lot of clarity, reassurance, and guidance. The tricky part is that these belief systems can vary widely, and it is hard to know which one is more correct than another or if some of them are even harmful.

What we do know is that most belief systems tend to agree that

“it is good to immerse oneself in the stream of life”.

People can try to find meaning through:

A. Hedonism: Seeking out pleasure and positive experiences and trying to avoid pain,

B. Altruism: Dedication towards a cause that helps other people, and

C. Creativity: Transcending oneself through art.

Many philosophers believe that both the search for pleasure and the search for meaning are paradoxical. By this, they mean that happiness and meaning or purpose in life are tough to achieve when they are aimed at directly, but possible if they are aimed at indirectly.

So if you or someone that you know is complaining about a lack of meaning in life, try to see if there are other issues. If possible, address these other issues first, and see if your worry about meaninglessness has lessened or gone away.

The best indirect way to increase a sense of purpose and meaning in life is to build kindness, curiosity and concern for others. This is often best done by helping out with a charity, joining a club, fighting for a cause, or attending a group activity or group therapy.

Yalom strongly believes that a desire to engage in life and satisfying relationships, work, spiritual and creative pursuits always exists within a person. Therefore, the key to managing meaninglessness is to remove the obstacles that prevent the individual from wholeheartedly engaging in the regular activities of life.

We may never be able to find the absolute meaning of life. However, what we can do is work at creating a life that is personally meaningful to us.

Dr Damon Ashworth

Clinical Psychologist

Interesting and thought provoking. Thank you for enlightening on these concerns.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you.

LikeLike

Beautiful article Dr

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved this one. Thanks!

On Fri, 25 Jan 2019, 07:35 Damon Ashworth Psychology Dr Damon Ashworth posted: “I’ve been afraid to say this for a while > because of how it will be perceived, but my favourite book of all time is > actually a textbook. Now before you think that makes me someone that you > would never want to speak to, I’ll ask if you have ever read anythi” >

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks 🙂

LikeLike

Oh, great post. Thank you. So packed with information, it should have been three posts!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating, insightful and useful. many thanks for taking the time to create this.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for the positive feedback!

LikeLike

Thank you for the recommendation. I’m certain you’ve read it given your field, but for those that haven’t, Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl is also stellar.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah it’s a great one. I put it as #1 in my top 20 psychology books countdown!

LikeLike

I seriously admire how much work you put on each post! It’s very inspiring. The part about Death really fascinated me. Honestly, I’ve always taken death as mercy for those who have done well, and, as you mentioned in this post, the fact that we know we are going to die, in my opinion, motivates us to fulfill our purposes and fix our mistakes before it’s too late.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is brilliant … it’s odd, but perhaps common that when I did nothing about a situation, I was in actual fact choosing to do nothing. I had choices and options, and I chose to do nothing. I chose not to confront the situation. I chose to listen to the excuses and blackmail and accept that I was in a bad situation. I chose to wait. Thank you for this post. It’s made me feel strength, strength in having the power to make choices. Katie

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Katie. I’m glad you found it helpful 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I absolutely did. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed reading this! Thank you for posting. Worth going back and reading again when I can take more of it in.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you!

LikeLike

“If we don’t know when we will die, being in touch with the fact that one day everything will vanish is enough to overwhelm some people and make them panic.” I’m a little confused by this statement. Does this mean that when I die, I will retain the ability to realize that “everything” has vanished, or will it simply be me that has vanished and everything else remains? To the best of my knowledge, no one has ever completely returned from “death” as we generalize the term to fully explain what happens.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry if it confusing. Yalom writes the book from a non-religious perspective. He assumes that as we lose brain activity when we die, we also lose consciousness, sensory input and awareness of everything. He believes that this thought of nothingness is scary for people when they are still alive, even though they wouldn’t be able to actually experience this nothingness once they have died. I hope that makes a bit more sense.

LikeLike

Having worked a number of years in EMS as a Paramedic, I’ve often wondered whether those I had to pronounce dead, were actually still able to process information. The rule of thumb, at least for me, became the level of cyanosis from the base of the neck up. If none was noted, I considered the patient to be viable and initiated immediate resusitative measures which continued until a Doctor was available to pronounce. Sometimes it was a rough call, especially in cases where there may be natural body gas causing involuntary muscle movement such as tics and eyelid flutter. There is a story about, I believe Voltaire, the French philosopher who, as a victim of the revolution was sentenced to be guillotined. He is alleged to have told his assistant to watch his eyes when his head was severed as he would blink if he still had control. Some think this BS, but as a Paramedic, I can attest that when the human body sustains a clean cut such as the Guillotine would administer, the blood vessels, which are actually under tension within the body, will retract into the body from the wound site thereby stemming the flood of bleeding for a short period of time. It is within this short period of time, my curiosity hangs. I do agree that the concept of “nothingness” is very scary, especially to those who are forced to be alone in their lives. To paraphrase, it become something more of my kingdom for a friend, rather than for a horse.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was really helpful and directly connected to real life, thanks

LikeLiked by 2 people

Such great information that I find immensely valuable. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awwe, you are welcome. 🌈

LikeLike

Fascinating topics. I don’t think Yalom got even a single mention at all during my studies. Quite a shame because from what little I’ve read of him, he seems very sound in his ideas, and he seems to have inspired clinicians who inspire me.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The only existentialist I ever liked even a little bit was Sartre and then probably coz of his war trilogy road to freedom but this was very concise, thoughtful and positive. Maybe that’s why Sartre was a somewhat fav of mine, with his own sideways positive take. Liked this a lot. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I used to think about death all the time. Now not so much. Great post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person